Case Study: Great Road Pottery of East Tennessee and Southwest Virginia

Great Road Pottery of East Tennessee and Southwest Virginia

Southern earthenware and stoneware research has made significant strides in the last 25 years. Entire new schools of pottery have been discovered, uncovering new forms and traditions. The pottery of the “Great Road”, encompassing Southwest Virginia and Eastern Tennessee represents a newly discovered pottery tradition.

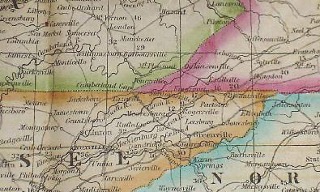

The Great Road region

The Great Road name was given to the primary route from Roanoke, Virginia to Eastern Tennessee. It was considered part of the “Great Wagon Road” initiating in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Moore, p.528). The regions of Southwest Virginia and Eastern Tennessee provided ideal earthenware production. There was an abundance of workable clays, a rapidly expanding population base during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and ease of transportation along the Great Road (Cullity, p. 62). Major pottery centers existed in Wytheville and Abingdon, Virginia and in Sullivan County of East Tennessee.

Great Road Pottery characteristics

Most clay forms of Great Road pottery were fired to a reddish-orange color. This color was the result of a high iron content in the clay at lower kiln temperatures. Most North Carolina Moravian wares were fired to a higher temperature and possessed a lower iron content, resulting in a buff color clay after firing.

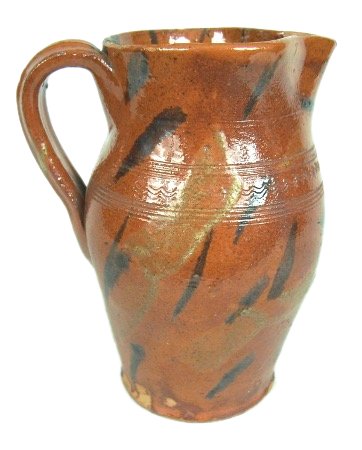

The pottery forms from this region are more heterogeneous than previously realized. Discoveries of bowls, pitchers, jars, and inkwells from this region display a variety of glazes and forms. Despite this, there are still common characteristics of forms and glazes that identify this pottery within the Great Road region.

Characteristics of Great Road redware include:

(2) When incising applied, sine waves and bands predominated.

(3) When handles applied, they are usually of the extruded type, ranging from two to five channels.

(4) Finger imprints are usually present at the handle terminal.

(5) Most common glazes include iron oxide, lead, and manganese. Copper oxide and yellow slip used to a lesser degree.

(6) Base usually unglazed.

Cain Pottery

Born in 1782, Leonard Cain started the Cain pottery in Blountville, Tennessee (Sullivan County). It is believed that he had migrated from the Valley of Virginia (Rodefer interview). Sullivan County deed records place him in the area no later than 1814 (Smith, p.55). Leonard’s sons, Abraham B. Cain and William Cain were also potters. William Cain’s son, Martin A. Cain, continued the pottery until the early 1900’s. Martin represented the last of the Cain dynasty. The Wolford and Henshaw families were married to members of the Cain family and assisted in the pottery operation.

Cain pottery jugs

Although the Cain pottery was in operation for greater than 75 years, the pottery forms changed little, if any, over this period. Indeed, once the dangers became well known about lead glazes, many potters converted to stoneware production. However, it appears that the Cains were producing retardataire redware forms until 1897 (latest dated piece).

Perhaps the glaze most identified with the Cain pottery was the lead glazed body with maganese splotching, resembling Connecticut earthenware. Additional glazes include maganese and iron oxide glazes. The earliest Cain jugs appear to have iron oxide glazes. Copper oxide glazes do not appear to have been used until the late 19th century at the pottery. Many Cain pieces consist of incised decorations that include sinewave (as many as three to four rows on some pieces) and/or banding on the bulbous midsection of most clay bodies. The fired clay bodies are invariably reddish-orange in appearance. This was the result of a lower firing temperature and higher iron content in the clay. The handles of Cain pieces were almost always of the extruded type. Finger prints are found at the handle terminals.

Examining shard evidence from the pottery site, it becomes readily apparent that the Cains experimented with other glazes not seen within the region or even within the South. Gold streaks have been observed on a couple of pitchers and jugs that has yet to be identified by the glaze that produced it. Other pieces have a yellow-brown speckled glaze that was previously unknown to be produced by the Cains.

Buying and selling investment quality pottery

If you have investment quality pottery and are considering selling, visit our selling page for more information.

If you are interested in acquiring earthenware from the Great Road region, sign up for our email list to be notified of upcoming auctions.

Bibliography

Books

Bivens, John Jr. The Moravian Potters in North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1972.

Comstock, H.E. The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Cullity, Brian. Slipped and Glazed: Regional American Redware, Hyannis, Massachusetts: Patriot Press, 1991.

Holston Territory Genealogical Society. Families and History of Sullivan County, Tennessee 1792-1992, Vol I, Waynesville, NC: Walsworth Publishing, 1992.

Smith, Samuel D. and Rogers, Steven T. A Survey of Pottery Making in Tennessee, Nashville: Division of Archaeology, Tennessee Department of Conservation, 1979.

Stradling, Diana and J. Garrison, editors. The Art of the Potter, New York: Main Street/Universe Books, 1977.

Magazines

Moore, J. Roderick. “Earthenware Potters Along The Great Road in Virginia and Tennessee,” The Magazine Antiques, September, 1983, pp. 528-537.

Maps

A map of the State of Virginia by Herman Boye. Philadelphia, engraved by H. S. Tanner, 1826. Corrected by order of the executive, 1859.

Mitchell’s Travelers Guide through the United States by J.H. Young. Philadelphia, published by S. Augustus Mitchell, 1836.